The other day when I posted a very positive review about a short story by David Naiman, I tweeted about it and included a notice to David. In turn, he posted a very kind thank you, retweeted it, and then a couple of people following him started following me. (I have 37 Twitter followers now! Imagine!)

Yesterday, Lisa Taddeo "liked" my Tweet linking to a positive review about her story A few weeks ago, I got an email from Eli Barrett when I blogged about his story. While blogging through Best American Short Stories, I got a reply on Twitter from Amy Silverberg, and Jacob Guajardo was cool enough to even follow me.

Posting positive reviews about writers, even if you run a blog that gets maybe 3,000 views a month, is a good way to make writer friends. And if you run a blog and are also a writer struggling to get picked up by a more noticeable venue, writer friends are good to have. Which means when I'm reviewing a story, I have only motivations to post positive reviews and no reason to post negative ones. That doesn't really promote honesty and healthy, vigorous criticism.

Naiman, when he responded on Twitter, noted that almost nobody is doing serious criticism of short stories these days. He's right, and I think I can understand why. Almost all the people reading short stories are writers themselves, so who in their right mind would provide honest criticism? Instead, what you're likely to get--and what we actually have--is an endless back-scratching chain of positive "reviews" that don't really review much. I say good things about you so you'll say good things about me. That's good for networking, but it's not great for the ecosystem of short fiction.

If there's a movie you like and you want to talk about it, you can easily find people online to talk about it with. You can find a dozen Youtubers picking apart the movie at length. If there's a song you like, you can find an online community to talk about it. But if you read a short story, and you want to dig into what it means or what works and doesn't work about it, you're usually shit out of luck. There's a reason I get 3,000 views a month; they're almost all headed to the reviews I've done. Almost nobody cares what I write about my own writing process. My blogging buddy Karen Carlson gets a lot more hits than I do, and she mostly is doing the same thing: reading short stories and talking about them. In fact, if you Google one of the short stories from BASS or Pushcart, she's usually the number one result after the story itself, and I'm often #2.

That's not a great sign for the health of short fiction as a viable commercial and cultural activity. Which is an absolute shame, because there is great fiction being written in America today, but almost the only stories anyone talks about, if they talk about them at all, are the ones the New Yorker puts out. And even that is usually just a day or two of chat on Twitter.

I find writing reviews somewhere between exhilarating and as exhausting as writing fiction of my own. It's definitely a lot more fun to write a good review than a bad one. The bad ones, I don't Tweet about. I feel bad about them. But I feel I need to write them, because without honest criticism, the ecosystem collapses.

Sunday, March 31, 2019

Saturday, March 30, 2019

A nearly perfect girl-girl buddy story: "A Suburban Weekend" by Lisa Taddeo

For the first three pages of Lisa Taddeo's "A Suburban Weekend," it's not clear who the main character is. Best friends Liv and Fern seem to have equal weight. They even seem to be near equals to each other when they compare who is more attractive, a pastime they seem to spend a lot of time on:

I had a hard time even remembering which was which for a while, although the story does its best to differentiate between the two early on. Before too long into the story, though, it's clear Fern's story is the central one. Not necessarily because she's the more interesting of the two, but because her needs are deeper.

Fern is depressed. Her parents are both dead, the second one in the last few months. The first look into her interior life we get, she is wanting "to be ground down." Fern has suicidal thoughts, and she is, as they say, "acting out" her feelings in increasingly dangerous, mostly sexual, ways.

She has become numb to most of her life. She has become "a person who didn't care who sat down beside her." The only instinct that survives in her is the one to be desired sexually: "The only thing that had lately survived in Fern was a desire to make men want to fuck her. All men. Every single man she saw. Hot dog vendors. UPS drivers across the street."

There are two remedies offered to Fern in "A Suburban Weekend": psychotropic drugs/therapy and love. The first one seems unlikely to work; the therapist is kind of a dick ("He wore knit ties on top of flannel shirts, like an executive who lived in a tree"), and Fern doesn't take the drugs they give her, anyway. So if there's a remedy that's going to work, it's got to be love.

The primary source of love, as opposed to sex, Fern gets is her best friend, Liv. Liv is a flawed friend. She's jealous of Fern. When Fern talks about her plans for suicide or says she feels like life is pointless, Liv deflects with humor (she's a comedian). Liv has plenty of issues of her own to work on--we find out she takes Adderall, although we don't know for what--and she's a hopeless romantic who spends her life in bars waiting for love to come along and fix all her problems. So it's going to be hard for Liv to be up to the challenge.

But Liv's also got a lot going for her as a friend. She honors the memory of Fern's parents, speaking to Fern in Fern's mother's voice, saying things she thinks Fern's mother would say (even if it's to say Fern looks like a slut in what she's wearing), and forcing food on her too-skinny friend like an Italian mother would.

Fern tells Liv about her plan to kill herself. Fern's been eating one of her mother's exotic Italian candies, lacrime d'amore, every time Fern does something stupid, like having sex with an Argentinian investor in the same room Liv is in. When Fern has gotten through all the candies, she's going to kill herself.

During the discussion where Fern reveals her plan, Liv, in a seemingly off-point comment about her desire for a husband, says she believes that "people can be saved by people who love them." This is the central conflict of the story: can Liv, with all her flaws, love Fern enough to save her? The meaning of lacrime d'amore is "tears of love." Liv, with all of her shortcomings, needs to somehow fill the bowl of love for Fern before Fern can exhaust it.

I usually don't worry about "spoilers" in a review/analysis of a short story. I figure people reading this have usually already read the story and are looking online for what someone else thought of it, rather than looking for a review to know if they should read it. But this once, I'm going to withhold giving away the ending, mostly because I found it to be something rare: a surprise ending that really worked and was genuinely moving.

There aren't a whole lot of girl-girl buddy stories out there. This is one of the best ones I've seen. It's up there with Danielle Evans's sort of accidental girl-girl buddy story "Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain." When telling a story, one has to take into consideration how much specificity an audience can handle. Do you batter your audience with little details of the life of your character, even things they may not be familiar with, or do you try to keep it to things everyone can understand? What's great about this story is that it doesn't shy away from specificity. It trusts that the readers will be able to handle details they may not be familiar with. Much like The Wire had universal appeal precisely because it dove so deeply into the local reality of Baltimore, this story succeeded by throwing everything about the life of a twenty-seven-year-old woman in New York City at the reader. It turns out that people really can relate new information to things they already know. I felt no obstacles to accessing the interior life of Fern because I'm a man in my forties.

It was a great story with a powerful central theme. Answering the question of whether love is enough to save someone is a story that will likely never get old. It certainly won't get old if it's handled with the skill this one was handled with.

Fern and Liv were always trying to decide who was prettier, hotter, who could bypass the line to et into Le Bain, who looked more elegant drinking cortados at a cafe with crossed legs. The answer flickered, depending on whether they were assessing themselves from far away or up close, and what each was wearing, how her hair looked, how much rest she'd gotten and, of course, who had recently been hit on hardest by tall guys with MBAs.

I had a hard time even remembering which was which for a while, although the story does its best to differentiate between the two early on. Before too long into the story, though, it's clear Fern's story is the central one. Not necessarily because she's the more interesting of the two, but because her needs are deeper.

Fern is depressed. Her parents are both dead, the second one in the last few months. The first look into her interior life we get, she is wanting "to be ground down." Fern has suicidal thoughts, and she is, as they say, "acting out" her feelings in increasingly dangerous, mostly sexual, ways.

She has become numb to most of her life. She has become "a person who didn't care who sat down beside her." The only instinct that survives in her is the one to be desired sexually: "The only thing that had lately survived in Fern was a desire to make men want to fuck her. All men. Every single man she saw. Hot dog vendors. UPS drivers across the street."

There are two remedies offered to Fern in "A Suburban Weekend": psychotropic drugs/therapy and love. The first one seems unlikely to work; the therapist is kind of a dick ("He wore knit ties on top of flannel shirts, like an executive who lived in a tree"), and Fern doesn't take the drugs they give her, anyway. So if there's a remedy that's going to work, it's got to be love.

|

| Can love save our hero? Stay tuned to find out! |

The primary source of love, as opposed to sex, Fern gets is her best friend, Liv. Liv is a flawed friend. She's jealous of Fern. When Fern talks about her plans for suicide or says she feels like life is pointless, Liv deflects with humor (she's a comedian). Liv has plenty of issues of her own to work on--we find out she takes Adderall, although we don't know for what--and she's a hopeless romantic who spends her life in bars waiting for love to come along and fix all her problems. So it's going to be hard for Liv to be up to the challenge.

But Liv's also got a lot going for her as a friend. She honors the memory of Fern's parents, speaking to Fern in Fern's mother's voice, saying things she thinks Fern's mother would say (even if it's to say Fern looks like a slut in what she's wearing), and forcing food on her too-skinny friend like an Italian mother would.

Fern tells Liv about her plan to kill herself. Fern's been eating one of her mother's exotic Italian candies, lacrime d'amore, every time Fern does something stupid, like having sex with an Argentinian investor in the same room Liv is in. When Fern has gotten through all the candies, she's going to kill herself.

During the discussion where Fern reveals her plan, Liv, in a seemingly off-point comment about her desire for a husband, says she believes that "people can be saved by people who love them." This is the central conflict of the story: can Liv, with all her flaws, love Fern enough to save her? The meaning of lacrime d'amore is "tears of love." Liv, with all of her shortcomings, needs to somehow fill the bowl of love for Fern before Fern can exhaust it.

I usually don't worry about "spoilers" in a review/analysis of a short story. I figure people reading this have usually already read the story and are looking online for what someone else thought of it, rather than looking for a review to know if they should read it. But this once, I'm going to withhold giving away the ending, mostly because I found it to be something rare: a surprise ending that really worked and was genuinely moving.

There aren't a whole lot of girl-girl buddy stories out there. This is one of the best ones I've seen. It's up there with Danielle Evans's sort of accidental girl-girl buddy story "Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain." When telling a story, one has to take into consideration how much specificity an audience can handle. Do you batter your audience with little details of the life of your character, even things they may not be familiar with, or do you try to keep it to things everyone can understand? What's great about this story is that it doesn't shy away from specificity. It trusts that the readers will be able to handle details they may not be familiar with. Much like The Wire had universal appeal precisely because it dove so deeply into the local reality of Baltimore, this story succeeded by throwing everything about the life of a twenty-seven-year-old woman in New York City at the reader. It turns out that people really can relate new information to things they already know. I felt no obstacles to accessing the interior life of Fern because I'm a man in my forties.

It was a great story with a powerful central theme. Answering the question of whether love is enough to save someone is a story that will likely never get old. It certainly won't get old if it's handled with the skill this one was handled with.

Thursday, March 28, 2019

The rant raised to high art: "Acceptance Speech" by David Naimon

David Naimon sets himself up with a tough challenge in "Acceptance Speech," originally published in Boulevard and now in the Pushcart Anthology. The entire story is told as an acceptance speech for an award. There is no set-up to the speech. We start with word one of the speech, and the story ends when the speech does. It's the sort of premise for a story that feels like it came out of one of those "writing prompt a day"calendars writers sometimes get as gifts. Whether it will work depends on the writer's ability to dazzle with one speech. The story stakes everything on the power of one soliloquy, told without breaks of any kind--not even paragraph breaks.

Fortunately, Naimon is up to the challenge. The narrator of "Acceptance Speech" mesmerizes her audience--us--right away, and the spell doesn't let up until the last word. She's winning some sort of award for gardening, of all things. Along the way to accepting her award, we learn about her philosophy and her relationship with her husband.

She doesn't think of gardening in the sentimental way one associates with gentle grandmothers and their funny gardening hats. Her speech is a "confession," which she likens to the gardener's tendency to go about "unearthing secrets, the subterranean love affair between taproots and earthworms, the unconquerable underground of morning glory networks, the white softness of larvae in the fetal position." Gardening isn't just about growing things to make the world beautiful to her. She sees through this lie into the heart of what gardening really is, just as she rejects the outward cuteness of otters by noting the truth that otters rape baby seals. (By the way, if you Google "otters rape baby seals," Google will shame you by reminding you that child pornography is illegal. Yes, Google. I agree. Please take me off your watch list.)

Gardening isn't about making the world beautiful. It's "an enterprise full of cruelty, a task best suited for sociopaths and tyrants...If not them, what mentality best suits a pastime where we alone choose what deserves to live and what deserves to die, that demands we constantly kill things to groom and nourish the others we prefer?"

Herein, shining through the philosophical rant, is the seed of actual human conflict in the story, the conflict between narrator and husband that seeps out through the speech. The husband is the cheery, optimistic sort. He recycles because he believes it might really save the planet, whereas the narrator, his wife, sees recycling as a "terrible lie," because it is nothing but a "Band-Aid on the open sore that is consumer capitalism." The narrator claims--and insists she means it--that the best solution would be to let humans be fully human and end their lives on Earth sooner rather than later, since it's inevitable we will wipe ourselves out eventually anyway.

The narrator looks to the bacteria that fill the soil she works in for an example, the bacteria she reminds her audience outnumber humans ten cells to one within our own bodies: "I say, let's look to our ancestors and to their ancestral wisdom for the answer. When we place bacteria in a petri dish with an abundant food supply, what happens? They reproduce rapidly, exponentially. They are unstoppable. That is, until they choke themselves to death on their own waste..."

So the narrator thinks humanity is doomed and refuses to be sentimental about it. The husband willfully refuses to see the truth the wife sees, which is why he wants kids and she doesn't. This leads us to the moment of crisis, when the husband confronts the wife by asking her: if you really think humanity is better off dying sooner rather than later, shouldn't you have kids? Shouldn't you have a ton of them? "That would be the ultimate act of filling the petri dish, wouldn't it?" he asks.

In anger, she tears out every beautiful plant in her garden and fills it with the most aesthetically challenged plants she can find. The Sambucus Black Tower. The Snakeroot.

When she has finally ripped out every plant in the garden, including the fig tree the couple had planted together as a symbol of "good luck and fertility," she realizes that this ugly reaction to her husband's insistent and childlike faith was "a terrible lie...a moral sleight of hand."

Her catharsis, her realization, is this: "That nothing did fulfill my philosophy more fully than hominid propagation, even if somehow it also, disturbingly, satisfied my husband's hackneyed hope for humanity's future as well."

She is content to "fill the petri dish." She is accepting the award for her strange garden, we learn, while pregnant. She adopts some of her husband's naivete during the goosebump-inducing peroration:

It's rare that short stories deal in such an honest way with what is really the central questions in life. There is a lot of modern fiction on questions of identity and social justice. These are important questions, of course, but they're not the central question. Nobody will care about social justice if she feels the world is doomed soon, anyway, or that humanity can never really rise about the essential red-in-tooth-and-clawness of nature. What was it that allowed the narrator of this story to embrace, however tentatively and with qualification, optimism for humanity's future?

The best I can tell, it was simply fully embracing the alternative. This is how some commentators read the Book of Ecclesiastes, too: after nihilistic thought piled on top of nihilistic thought, the "preacher"--who is, just like Naimon's narrator, telling a story through a speech--finally collapses into a tried-and-true chestnut of a conclusion. "Here is the conclusion of the matter: fear God and keep His commandments." It's not a very convincing conclusion after so much despair, perhaps, unless you accept that the preacher has earned his soft landing after so much unblinking honesty.

Some people, like the narrator's husband, naturally lean toward optimism. They do so by ignoring many inconvenient facts, but by the end the narrator doesn't see this as something to despise the optimistic for. She also arrives at a well-worn conclusion: go forth and multiply. For her, it isn't so much a surrender after having been though the dark night of the soul as it is a realization that nihilism and optimism, on some level, come out to the same thing.

She has repeated a process our ancestors no doubt had to find for themselves long ago. Some poor soul in the neolithic period, scratching out a tough life from the ground, decided to grow something because it was beautiful. This first gardener was not unaware of how brutal nature really was, how ready to kill. This understanding of what nature really was wasn't a challenge to optimism; it was the source of it. The narrator in "Acceptance Speech" is just repeating an ancient discovery by means of the act of accepting something being given to her.

Fortunately, Naimon is up to the challenge. The narrator of "Acceptance Speech" mesmerizes her audience--us--right away, and the spell doesn't let up until the last word. She's winning some sort of award for gardening, of all things. Along the way to accepting her award, we learn about her philosophy and her relationship with her husband.

She doesn't think of gardening in the sentimental way one associates with gentle grandmothers and their funny gardening hats. Her speech is a "confession," which she likens to the gardener's tendency to go about "unearthing secrets, the subterranean love affair between taproots and earthworms, the unconquerable underground of morning glory networks, the white softness of larvae in the fetal position." Gardening isn't just about growing things to make the world beautiful to her. She sees through this lie into the heart of what gardening really is, just as she rejects the outward cuteness of otters by noting the truth that otters rape baby seals. (By the way, if you Google "otters rape baby seals," Google will shame you by reminding you that child pornography is illegal. Yes, Google. I agree. Please take me off your watch list.)

|

| Assholes. |

Gardening isn't about making the world beautiful. It's "an enterprise full of cruelty, a task best suited for sociopaths and tyrants...If not them, what mentality best suits a pastime where we alone choose what deserves to live and what deserves to die, that demands we constantly kill things to groom and nourish the others we prefer?"

Herein, shining through the philosophical rant, is the seed of actual human conflict in the story, the conflict between narrator and husband that seeps out through the speech. The husband is the cheery, optimistic sort. He recycles because he believes it might really save the planet, whereas the narrator, his wife, sees recycling as a "terrible lie," because it is nothing but a "Band-Aid on the open sore that is consumer capitalism." The narrator claims--and insists she means it--that the best solution would be to let humans be fully human and end their lives on Earth sooner rather than later, since it's inevitable we will wipe ourselves out eventually anyway.

The narrator looks to the bacteria that fill the soil she works in for an example, the bacteria she reminds her audience outnumber humans ten cells to one within our own bodies: "I say, let's look to our ancestors and to their ancestral wisdom for the answer. When we place bacteria in a petri dish with an abundant food supply, what happens? They reproduce rapidly, exponentially. They are unstoppable. That is, until they choke themselves to death on their own waste..."

So the narrator thinks humanity is doomed and refuses to be sentimental about it. The husband willfully refuses to see the truth the wife sees, which is why he wants kids and she doesn't. This leads us to the moment of crisis, when the husband confronts the wife by asking her: if you really think humanity is better off dying sooner rather than later, shouldn't you have kids? Shouldn't you have a ton of them? "That would be the ultimate act of filling the petri dish, wouldn't it?" he asks.

In anger, she tears out every beautiful plant in her garden and fills it with the most aesthetically challenged plants she can find. The Sambucus Black Tower. The Snakeroot.

|

| A Sambucus Black Tower. All I can see is the singing bush from Three Amigos. |

When she has finally ripped out every plant in the garden, including the fig tree the couple had planted together as a symbol of "good luck and fertility," she realizes that this ugly reaction to her husband's insistent and childlike faith was "a terrible lie...a moral sleight of hand."

Her catharsis, her realization, is this: "That nothing did fulfill my philosophy more fully than hominid propagation, even if somehow it also, disturbingly, satisfied my husband's hackneyed hope for humanity's future as well."

She is content to "fill the petri dish." She is accepting the award for her strange garden, we learn, while pregnant. She adopts some of her husband's naivete during the goosebump-inducing peroration:

"I..watch a fat tiger-striped slug slide in the moonlight. I decide not to scissor it. Not yet. I decide to leave it whole, as my husband would prefer, leave it unsplit, undivided for yet another moment. But the hum, it is unmistakable. I like to think it is both that I hear, the bacteria and me, the hum of our division, as together we feed the fever and add to the dish. The garden and I, we are so full, so full of life. Thank you for this great honor."

It's rare that short stories deal in such an honest way with what is really the central questions in life. There is a lot of modern fiction on questions of identity and social justice. These are important questions, of course, but they're not the central question. Nobody will care about social justice if she feels the world is doomed soon, anyway, or that humanity can never really rise about the essential red-in-tooth-and-clawness of nature. What was it that allowed the narrator of this story to embrace, however tentatively and with qualification, optimism for humanity's future?

The best I can tell, it was simply fully embracing the alternative. This is how some commentators read the Book of Ecclesiastes, too: after nihilistic thought piled on top of nihilistic thought, the "preacher"--who is, just like Naimon's narrator, telling a story through a speech--finally collapses into a tried-and-true chestnut of a conclusion. "Here is the conclusion of the matter: fear God and keep His commandments." It's not a very convincing conclusion after so much despair, perhaps, unless you accept that the preacher has earned his soft landing after so much unblinking honesty.

Some people, like the narrator's husband, naturally lean toward optimism. They do so by ignoring many inconvenient facts, but by the end the narrator doesn't see this as something to despise the optimistic for. She also arrives at a well-worn conclusion: go forth and multiply. For her, it isn't so much a surrender after having been though the dark night of the soul as it is a realization that nihilism and optimism, on some level, come out to the same thing.

She has repeated a process our ancestors no doubt had to find for themselves long ago. Some poor soul in the neolithic period, scratching out a tough life from the ground, decided to grow something because it was beautiful. This first gardener was not unaware of how brutal nature really was, how ready to kill. This understanding of what nature really was wasn't a challenge to optimism; it was the source of it. The narrator in "Acceptance Speech" is just repeating an ancient discovery by means of the act of accepting something being given to her.

Monday, March 25, 2019

The need for speed in reviews:

I was talking today with a friend about the movie Get Out, since Us just came out. I wrote about it two years ago when it came out, but I still don't really know what I think about it. I also talked with Mrs. Heretic this weekend about the recent remake of A Star is Born. I can't decide if it was a really good movie or just a so-so movie with two really amazing performances. I saw the movie months ago, but still can't make my mind up.

It takes a while for a story to marinate before I can really ingest it. So why do I read a story one day and review/analyze it the next? I guess for the same reason movie or video game reviewers have to post the moment something comes out. It's not quite as urgent for me--it's not like a book has the same life-span as a movie. But if I'm going to get through all of Pushcart or Best American Short Stories, I kind of need to keep moving. So I read, re-read, and then write.

I don't believe most people really have enough perspective on stories after a day to get to the heart of them. If all you need to do is give a thumbs-up/thumbs-down on going to see it, that's probably not a problem, but reviewers try to get to the heart of stories all the time without having spent enough time to really see what that story is about.

I'm just wondering how much I'm doing it.

This isn't an excuse, by the way, for how long it's taking me to do my next review. That's more because I have another project I'm working on. It's just something that's on my mind. It's not like I've spent no time or effort trying to get to the bottom of a story, but I do wonder what the right mix of time vs. timeliness is to be effective as a critic.

It takes a while for a story to marinate before I can really ingest it. So why do I read a story one day and review/analyze it the next? I guess for the same reason movie or video game reviewers have to post the moment something comes out. It's not quite as urgent for me--it's not like a book has the same life-span as a movie. But if I'm going to get through all of Pushcart or Best American Short Stories, I kind of need to keep moving. So I read, re-read, and then write.

I don't believe most people really have enough perspective on stories after a day to get to the heart of them. If all you need to do is give a thumbs-up/thumbs-down on going to see it, that's probably not a problem, but reviewers try to get to the heart of stories all the time without having spent enough time to really see what that story is about.

I'm just wondering how much I'm doing it.

This isn't an excuse, by the way, for how long it's taking me to do my next review. That's more because I have another project I'm working on. It's just something that's on my mind. It's not like I've spent no time or effort trying to get to the bottom of a story, but I do wonder what the right mix of time vs. timeliness is to be effective as a critic.

Monday, March 18, 2019

Puzzling parable: "The Wall" by Robert Coover

I'm a fan of parables and fables. They are a sadly neglected form these days, largely because anything that smacks of didacticism is suspect. "The Wall" by Robert Coover partly escapes being charged with being didactic by also being enigmatic, although doing so robs it of much of the pleasure that comes with a true parable.

It's a simple story and a short one, and it can be separated into four parts. Two lovers, highly reminiscent of Pyramus and Thisbe from mythology, fall in love with one another while building a wall to separate their two towns. The town fathers of both rival cities have assured their citizens that only a wall can give them freedom, a freedom that requires discipline and sacrifice. In part two, resistance to the wall mounts. The lovers, who had begun their resistance because of their desire to be together, change during this part and begin to focus on knocking the wall down more than on why they wanted to knock it down: "There was no time now for stolen glances, passionate whispers into the wall; the fall of the wall became their life's project, their existence all but defined by it."

After the fall of the wall, we move into part three, in which the lovers realize that, strange as it may be, they miss the wall. The wall had deprived them of their desires, but also been "a stimulus to them." Freedom, however, "had deprived them of their intensity." In part four, the lovers and others who lived through the age of the wall begin to erect a psychological wall, one only they can see. They speak to each other over this imaginary wall.

It is during this fourth stage that the lovers engage in a somewhat stream-of-consciousness dialogue with one another, one in which the lovers, now divorced, try to come to terms with the meaning of the lives they have lived:

So is there a moral, even if it's one the lovers are running from? Whatever the moral may be, it's not a comforting one. They realize they have been using the wall to shield themselves "from anything more disquieting than banter." The moral is something about the "tyranny of time," that walls are destined to be knocked down and rebuilt, but emptiness will last through it all.

Pyramus and Thisbe from legend both killed themselves in an act of tragic misunderstanding. The lovers in Coover's story seem to run from the meaning of the story of their lives in order to prevent a kind of death overtaking them. They recall being told that the wall meant freedom, and now that they feel only loneliness, they wonder if that loneliness itself is the freedom they had been promised.

I didn't find this a terribly enjoyable or insightful story. It's the kind of story a beginning writing student would write. In fact, I wrote one a lot like it 20 years ago. It would never have been published for anyone without a track record, or if it had, it would have been ignored. The parable structure is really nothing more than a cheap excuse to avoid writing a more fleshed-out world or coming up with a narrative where anything is more than just roughly sketched out. You start off wishing for something for a reason, then the something itself becomes the reason, and then you feel empty when you finally get it. That's a pretty familiar story. I don't think the parable form of story really has much to do here. It's not its natural place to shine.

It's a simple story and a short one, and it can be separated into four parts. Two lovers, highly reminiscent of Pyramus and Thisbe from mythology, fall in love with one another while building a wall to separate their two towns. The town fathers of both rival cities have assured their citizens that only a wall can give them freedom, a freedom that requires discipline and sacrifice. In part two, resistance to the wall mounts. The lovers, who had begun their resistance because of their desire to be together, change during this part and begin to focus on knocking the wall down more than on why they wanted to knock it down: "There was no time now for stolen glances, passionate whispers into the wall; the fall of the wall became their life's project, their existence all but defined by it."

|

| I don't know whether Pyramus or Thisbe's parents paid for the wall. |

After the fall of the wall, we move into part three, in which the lovers realize that, strange as it may be, they miss the wall. The wall had deprived them of their desires, but also been "a stimulus to them." Freedom, however, "had deprived them of their intensity." In part four, the lovers and others who lived through the age of the wall begin to erect a psychological wall, one only they can see. They speak to each other over this imaginary wall.

It is during this fourth stage that the lovers engage in a somewhat stream-of-consciousness dialogue with one another, one in which the lovers, now divorced, try to come to terms with the meaning of the lives they have lived:

Though monstrous, the old wall gave so much meaning to our lives, one said, and the other: Well, meaning, that old delusion. Which, when sought, is just another form of nostalgia. Sort of like love, you mean. No, love, whatever it is, is real in its stupefying way. But it's not enough. No, and there's not much else. That's very sad. It is. Sometimes I cry. We had some good parties, though, which wouldn't have happened without a wall in the way. There's probably a moral, but I don't want to know it.

So is there a moral, even if it's one the lovers are running from? Whatever the moral may be, it's not a comforting one. They realize they have been using the wall to shield themselves "from anything more disquieting than banter." The moral is something about the "tyranny of time," that walls are destined to be knocked down and rebuilt, but emptiness will last through it all.

Pyramus and Thisbe from legend both killed themselves in an act of tragic misunderstanding. The lovers in Coover's story seem to run from the meaning of the story of their lives in order to prevent a kind of death overtaking them. They recall being told that the wall meant freedom, and now that they feel only loneliness, they wonder if that loneliness itself is the freedom they had been promised.

I didn't find this a terribly enjoyable or insightful story. It's the kind of story a beginning writing student would write. In fact, I wrote one a lot like it 20 years ago. It would never have been published for anyone without a track record, or if it had, it would have been ignored. The parable structure is really nothing more than a cheap excuse to avoid writing a more fleshed-out world or coming up with a narrative where anything is more than just roughly sketched out. You start off wishing for something for a reason, then the something itself becomes the reason, and then you feel empty when you finally get it. That's a pretty familiar story. I don't think the parable form of story really has much to do here. It's not its natural place to shine.

Saturday, March 16, 2019

White privilege through a prism...and then a blender: "The Whitest Girl" by Brenda Peynado

The most satisfying kind of story analyses for me are the ones where I feel like I've stated some kind of half-reasonable theme about a story. A theme, to wax pedantic for a second, is not the same as a subject. "Friendship" is not a theme. The story's attitude toward friendship is a theme, something like, "Friendship can be a solace, but also an anchor." While realizing that no statement of a theme is actually the theme itself--else, why would there be a need for a story?--it does feel more to me like I've done my work of analysis when I can at least arrive in the vicinity of some kind of thematic statement.

That's what makes Brenda Peynado's "The Whitest Girl" both such a joy and a frustration to work with. There's all kinds of mortar to build a thematic house from, but there seem to be eleven different blueprints within the story.

That's actually a good thing. This is an absolutely electric story; it's pulsing with raw power. I don't think the writer is even fully in control of the power of this story, which actually adds to its appeal. She's writing about the intersection of race, class, and gender in America, which is about as explosive a topic as we have today. It wouldn't be nearly as interesting if all the powder kegs were kept away from the flames. Part of what made this story so instantly satisfying was watching the writer's Zippo get close to the barrels of dynamite over and over, wondering when things were finally going to blow.

But how to wrangle this explosiveness into some kind of statement of theme, some hint of "what it's really about"? You can't approach this story head-on; it will take a little bit of a roundabout approach. I think it might be good to start with why this story is enjoyable first, then extrapolate from what's enjoyable about it to what's meaningful.

The story is about a white girl who comes from a poor family and attends a majority Latino high school. She deals with prejudice, both the well-meaning and the not-so-well-meaning kinds, in a flip-the-script story about race. It called to mind a bad film from the 90s, one that had much higher ambitions than it achieved. The film was White Man's Burden. Essentially, it just took the familiar racial situation in America and flipped it--it was an alternate universe in which whites had historically been subjugated to blacks, and were now, although in some ways better off than they had been, still dealing with the legacy of racism.

The movie didn't really work for me. It has a 24% on Rotten Tomatoes, so apparently I'm not alone. It failed because flipping the script didn't really tell us anything new about racism. It told exactly the same story, just transcribed into a different color scheme. I think the point was to maybe shame white people into suddenly taking racism seriously, as though the sort of people who had stoutly resisted claims that black people still had it bad would suddenly, by seeing a white person have trouble finding a white doll for his kid, change their minds about everything. It was a little condescending and more than a little moralizing.

"Whitest Girl" isn't an alternate universe. It's this world, just a corner of it where racism's logic operates a little differently. White privilege still exists, but this is about a place in the world where one white person is definitely at the bottom of the social hierarchy. It's tempting to be hasty and say the theme of the story is that if the world were reversed and privilege granted to another race, then that race would act much the same as whites do in their current role. But while that may be a tiny bit of what this story's about, it's way more complicated than that. It is, in fact, extremely difficult to make the story lie still long enough to pick out a consistent attitude about race in it.

One reason why is the incredibly effective use of the first-person plural ("we") narrator. "We" are the ones interacting with Terry, the white girl whose parents died and who heads home to a trailer to take care of her many siblings. While one part of "We" might by sympathetic toward Terry, there is always another voice that comes in to complicate what "We" collectively think about her.

The "we" narrator calls Terry a "Frankenstein cobbled together," but so is the narrator. That's why "We" can't really decide either what Terry means or what Terry teaches us. She is "made of what we hated, what hated us, the disinterest and disregard that bunched us together with these disgusting people, with their potatoes and bad music, bad manners, their self-satisfied boredom." From the moment "We" come in contact with Terry, "We" cannot decide what she signifies for us. "We" decide to follow her wherever she goes in order to make sense of her, but the project is doomed from the beginning:

The group cannot decide on the meaning of its surveillance or its aim right at the beginning, so it's no wonder they cannot agree on what they learn from the surveillance. There are a couple of notes the group keeps hitting, however. One is that they are resentful. Although it's clear Terry is poor--poorer than any of them--they still associate Terry with the people who "yelled at us in the grocery store, or assumed we couldn't speak English, or that we were somehow unintelligent." A second reoccurring idea is that Terry wants to be one of them. When they see her stop in the parking lot and almost look back at them, "We" think that "this meant that she wanted to be a part of our lives, that she regretted never inviting us over to her squalid trailer..."

"We" are torn between hating her for reminding us of other white people in society who have privileges we don't share. "We" also look down on her for having less than us, and, assuming she wishes she could be us, work to keep her excluded. Meanwhile, a few of us try to look at her with sympathy.

The notion of white privilege is a key concept in American culture right now. It's also a contentious one. Although most white people would probably concede that being white is, on the whole, more of an advantage than a disadvantage, if you happen to come across a white person who grew up poor or with shaky parents, they will likely bristle at the notion that they had it easy because they were white. They would say that yes, whiteness helps, but the benefits of whiteness can be offset by other things.

In this story, we have Terry's whiteness, which "We" go so far as to call "audacious" whiteness, pitted against her poverty. In society as a whole, being white brings privilege, but in the corner of society in this story, Terry is the other, Terry is the one with no privileges. So while "We" are figuring out what to do with Terry, the whole notion of white privilege is being interrogated by taking it out of its general context and putting it in a very specific exception.

"We" end up with a decision to make. Terry has started dating the janitor of the high school. "We" are all jealous. Ironically, "We" resent the janitor's refusal to treat us in the exotic and sexually stereotyped way Latina women are sometimes treated: "What magic did she have that none of us did? ...We were the color of smooth pecans, our eyes dark and full of mysteries, our plump lips deep purple and moistened." It's maddening to the girls that the janitor doesn't treat them as idealized abstractions, isn't impressed by their "stories about how our families had crossed this ocean or that desert or were pursued by an evil dictator." He has picked the plain white girl, and this shall not stand.

The girls decide to pry Terry away from the janitor in order to ruin their relationship by inviting her to one of the girls' quinceanera. But at the party, they learn a startling fact from one of the older boys there: the janitor was kicked out of his high school for raping a white girl at a party under circumstances almost exactly like the ones Terry is in at the moment. The girls have to figure out what to do. In that moment, it turns out that the nice thing to do and the mean thing to do coincide, so the divided "We" at last can agree on a plan. They finally manage to break the two up, although by the end it's not entirely clear the janitor was really justly accused.

This is likely to be a story that everyone brings their pre-existing ideas of race to. Some people will say it proves that anyone can be a racist given the right conditions. Some will say it proves that white privilege is either a real thing or not such a real thing. Some will say that it merely shows that racial relations are more complicated than we think.

I think a large point of the underlying theme is related to the ever-shifting "We." Some parts of "We" seem to be kind. Some are obviously not kind. In the end, they get the janitor away from Terry, but it's not clear if they did it for good reasons, and it's not clear they even did the right thing. It will never be clear, because "We" is so riven, so full of contradictions, it's hard to figure out what is really motivating the group in power in this story.

And there's the theme. In the larger societal context, in which white people really do have some measure of privilege, white people often complain when blanket accusations are thrown at them. "Not all white people are racist!" they claim. They are, of course, right. But the problem is that "we" white people really are a "We." We may not think of ourselves as a group, but we seem that way to those outside our group. Within our "We," we're many voices, some good, some bad, and we can't even agree on what we all think. And many actions "We" take could conceivably have good or bad motives, such as putting drug offenders behind bars in record numbers. Is this to protect vulnerable black families, or to punish them?

When "We" are of so many different minds, it is impossible for outside groups to make judgments about our motives. While the dominant group watches outside groups to try to understand them, they are watching back. Like the reader in this story, every attempt of someone outside the group in power will be frustrated in an attempt to draw meaning by the sheer abundance of different meanings the "We" is constructing at any time.

Terry decides to go off and live as a cloistered at the end. I'm not sure that's a totally satisfying resolution to the story, but it is a reasonable resolution for outsiders to decide to withdraw from the society they can never hope to comprehend because it does not comprehend itself.

That's what makes Brenda Peynado's "The Whitest Girl" both such a joy and a frustration to work with. There's all kinds of mortar to build a thematic house from, but there seem to be eleven different blueprints within the story.

That's actually a good thing. This is an absolutely electric story; it's pulsing with raw power. I don't think the writer is even fully in control of the power of this story, which actually adds to its appeal. She's writing about the intersection of race, class, and gender in America, which is about as explosive a topic as we have today. It wouldn't be nearly as interesting if all the powder kegs were kept away from the flames. Part of what made this story so instantly satisfying was watching the writer's Zippo get close to the barrels of dynamite over and over, wondering when things were finally going to blow.

But how to wrangle this explosiveness into some kind of statement of theme, some hint of "what it's really about"? You can't approach this story head-on; it will take a little bit of a roundabout approach. I think it might be good to start with why this story is enjoyable first, then extrapolate from what's enjoyable about it to what's meaningful.

Contrast to a similar idea that didn't work

The story is about a white girl who comes from a poor family and attends a majority Latino high school. She deals with prejudice, both the well-meaning and the not-so-well-meaning kinds, in a flip-the-script story about race. It called to mind a bad film from the 90s, one that had much higher ambitions than it achieved. The film was White Man's Burden. Essentially, it just took the familiar racial situation in America and flipped it--it was an alternate universe in which whites had historically been subjugated to blacks, and were now, although in some ways better off than they had been, still dealing with the legacy of racism.

The movie didn't really work for me. It has a 24% on Rotten Tomatoes, so apparently I'm not alone. It failed because flipping the script didn't really tell us anything new about racism. It told exactly the same story, just transcribed into a different color scheme. I think the point was to maybe shame white people into suddenly taking racism seriously, as though the sort of people who had stoutly resisted claims that black people still had it bad would suddenly, by seeing a white person have trouble finding a white doll for his kid, change their minds about everything. It was a little condescending and more than a little moralizing.

|

| Maybe it just needed a dash of Tarantino in it to make it work. |

What "Whitest Girl" did differently

"Whitest Girl" isn't an alternate universe. It's this world, just a corner of it where racism's logic operates a little differently. White privilege still exists, but this is about a place in the world where one white person is definitely at the bottom of the social hierarchy. It's tempting to be hasty and say the theme of the story is that if the world were reversed and privilege granted to another race, then that race would act much the same as whites do in their current role. But while that may be a tiny bit of what this story's about, it's way more complicated than that. It is, in fact, extremely difficult to make the story lie still long enough to pick out a consistent attitude about race in it.

One reason why is the incredibly effective use of the first-person plural ("we") narrator. "We" are the ones interacting with Terry, the white girl whose parents died and who heads home to a trailer to take care of her many siblings. While one part of "We" might by sympathetic toward Terry, there is always another voice that comes in to complicate what "We" collectively think about her.

The "we" narrator calls Terry a "Frankenstein cobbled together," but so is the narrator. That's why "We" can't really decide either what Terry means or what Terry teaches us. She is "made of what we hated, what hated us, the disinterest and disregard that bunched us together with these disgusting people, with their potatoes and bad music, bad manners, their self-satisfied boredom." From the moment "We" come in contact with Terry, "We" cannot decide what she signifies for us. "We" decide to follow her wherever she goes in order to make sense of her, but the project is doomed from the beginning:

We wanted to know Terry's secrets, we wanted to know who she loved, who she hated, what she dreamed of in the bed she shared with her sisters. This is not what we admitted to each other, of course. We said that we hated her, we wanted to ruin her life, or at least get her kicked out of school, and haz mel favor, how dare she?...Some of us protested at our cruelty, but the rest of us framed it as a game. Then it all seemed harmless.

The group cannot decide on the meaning of its surveillance or its aim right at the beginning, so it's no wonder they cannot agree on what they learn from the surveillance. There are a couple of notes the group keeps hitting, however. One is that they are resentful. Although it's clear Terry is poor--poorer than any of them--they still associate Terry with the people who "yelled at us in the grocery store, or assumed we couldn't speak English, or that we were somehow unintelligent." A second reoccurring idea is that Terry wants to be one of them. When they see her stop in the parking lot and almost look back at them, "We" think that "this meant that she wanted to be a part of our lives, that she regretted never inviting us over to her squalid trailer..."

"We" are torn between hating her for reminding us of other white people in society who have privileges we don't share. "We" also look down on her for having less than us, and, assuming she wishes she could be us, work to keep her excluded. Meanwhile, a few of us try to look at her with sympathy.

What's at stake

The notion of white privilege is a key concept in American culture right now. It's also a contentious one. Although most white people would probably concede that being white is, on the whole, more of an advantage than a disadvantage, if you happen to come across a white person who grew up poor or with shaky parents, they will likely bristle at the notion that they had it easy because they were white. They would say that yes, whiteness helps, but the benefits of whiteness can be offset by other things.

In this story, we have Terry's whiteness, which "We" go so far as to call "audacious" whiteness, pitted against her poverty. In society as a whole, being white brings privilege, but in the corner of society in this story, Terry is the other, Terry is the one with no privileges. So while "We" are figuring out what to do with Terry, the whole notion of white privilege is being interrogated by taking it out of its general context and putting it in a very specific exception.

How it resolves

"We" end up with a decision to make. Terry has started dating the janitor of the high school. "We" are all jealous. Ironically, "We" resent the janitor's refusal to treat us in the exotic and sexually stereotyped way Latina women are sometimes treated: "What magic did she have that none of us did? ...We were the color of smooth pecans, our eyes dark and full of mysteries, our plump lips deep purple and moistened." It's maddening to the girls that the janitor doesn't treat them as idealized abstractions, isn't impressed by their "stories about how our families had crossed this ocean or that desert or were pursued by an evil dictator." He has picked the plain white girl, and this shall not stand.

The girls decide to pry Terry away from the janitor in order to ruin their relationship by inviting her to one of the girls' quinceanera. But at the party, they learn a startling fact from one of the older boys there: the janitor was kicked out of his high school for raping a white girl at a party under circumstances almost exactly like the ones Terry is in at the moment. The girls have to figure out what to do. In that moment, it turns out that the nice thing to do and the mean thing to do coincide, so the divided "We" at last can agree on a plan. They finally manage to break the two up, although by the end it's not entirely clear the janitor was really justly accused.

What it all means

This is likely to be a story that everyone brings their pre-existing ideas of race to. Some people will say it proves that anyone can be a racist given the right conditions. Some will say it proves that white privilege is either a real thing or not such a real thing. Some will say that it merely shows that racial relations are more complicated than we think.

I think a large point of the underlying theme is related to the ever-shifting "We." Some parts of "We" seem to be kind. Some are obviously not kind. In the end, they get the janitor away from Terry, but it's not clear if they did it for good reasons, and it's not clear they even did the right thing. It will never be clear, because "We" is so riven, so full of contradictions, it's hard to figure out what is really motivating the group in power in this story.

And there's the theme. In the larger societal context, in which white people really do have some measure of privilege, white people often complain when blanket accusations are thrown at them. "Not all white people are racist!" they claim. They are, of course, right. But the problem is that "we" white people really are a "We." We may not think of ourselves as a group, but we seem that way to those outside our group. Within our "We," we're many voices, some good, some bad, and we can't even agree on what we all think. And many actions "We" take could conceivably have good or bad motives, such as putting drug offenders behind bars in record numbers. Is this to protect vulnerable black families, or to punish them?

When "We" are of so many different minds, it is impossible for outside groups to make judgments about our motives. While the dominant group watches outside groups to try to understand them, they are watching back. Like the reader in this story, every attempt of someone outside the group in power will be frustrated in an attempt to draw meaning by the sheer abundance of different meanings the "We" is constructing at any time.

Terry decides to go off and live as a cloistered at the end. I'm not sure that's a totally satisfying resolution to the story, but it is a reasonable resolution for outsiders to decide to withdraw from the society they can never hope to comprehend because it does not comprehend itself.

Wednesday, March 13, 2019

This has now gotten ridiculous

From the Georgia Review, received today:

"Although your manuscript engaged our attention through several screenings, it was not ultimately selected for publication."

This is the Georgia motherhumpin' Review. One of the best journals on the planet. It now joins these other fine journals in having told me they were very close to accepting this particular story, but not quite there:

"Although your manuscript engaged our attention through several screenings, it was not ultimately selected for publication."

This is the Georgia motherhumpin' Review. One of the best journals on the planet. It now joins these other fine journals in having told me they were very close to accepting this particular story, but not quite there:

- Carve

- The Iowa Reivew

- The Common

- Shenandoah

- Nashville Review

That's six journals, any of which would have been a tremendous breakthrough for me, all of whom said they found a lot to like in it, but it wasn't quite there.

I just don't know what to do anymore. As a reader, I look at this story and feel like I just nailed it. I think it's the best thing I've ever written. It's much better than the stories I've published before. It's on a topic that's in the news, and I quite likely have more insight into this topic than any writer out there. If there's a story I really have to tell the world that's worth a damn, this is it. But it's a long story, which means there are a limited number of places to send it to, and I've sent it to almost all of them by now. I have a few more to try, but why would I expect anything different?

I gave it another look this week. I see I had two sections early on where I messed up sentences during a prior edit. That might have hurt its chances, although anyone who got past those enough to read the whole thing probably didn't say no because of those. My judgment as a reader is that the thing is pretty much right as it stands. There doesn't seem to me to be anything more to do with it.

I talk a lot about giving up, but I really don't want to. I love this story. It deserves readers. But if I can't get this one published, what chance do I have of ever having any kind of real audience as a writer? If I'm wrong about this story, I literally have no idea what's worth reading.

I can't believe a story can be considered good by so many journals of sound judgement, but not good enough by any.

Jesus, if I ever have some kind of definitive breakthrough and am looking back through this blog for moments of despair where it didn't look like it was ever going to happen, this is about as dark a one of those moments as I've felt.

Tuesday, March 12, 2019

An Analysis of "I Figure" by Kim Chinquee, followed by some thoughts on the place of flash fiction in American literature

For the second time in a row, one of the stories from the 2019 Pushcart Anthology immediately make me think of thematically similar story from the 2018 Best American Short Stories anthology. This time, however, I think it's the BASS story that comes off looking like the better of the two.

Kim Chinquee's "I Figure" hits similar thematic ground to "Los Angeles" by Emma Cline, which appeared in the 2018 BASS. Both stories center around young women, 20's-ish, who are making use too liberally of "you only live once" or "you learn by making mistakes, so make big mistakes" kinds of advice.

Chinquee's story is flash fiction, so it doesn't have much time to develop theme (or anything else). It relies on one scene and the imagery evoked in that scene. The narrator is lying on her back, post-coitally, balancing a glass of white wine on her abdomen while her lover the heart surgeon goes off to the bathroom to remove his condom and do the other after-sex things men do.

The act of balancing the wine glass tells the reader two things. First, she's in shape, because she's calling her stomach her "abs" and flexing in order to balance the glass. These are the sorts of things someone used to long rounds of ab exercises would do. She's likely someone who works out a lot in order to be attractive, rather than for personal reasons. We know she's had a lot of boyfriends, because she recalls taking a dog out "first with one boyfriend, then another, then another."

There are three refrains of "I figure" in the story. Twice it's to say she figures what she's doing is harmless. At the end, the formula shifts, and the narrator says she figures she's harmless. With each "I figure," the level of protesting too much grows.

It's a story of a woman making, perhaps, a few too many mistakes. The narrative arc doesn't happen on screen. We figure it will likely happen soon after this story is over. What we see in "I Figure" is a woman who's been deceiving herself, but her justifications are starting to become less convincing to herself. This might be the last time she does something self-destructive and calls it "harmless."

Or, maybe, this is the final act of defeating her own inner voice telling her to get her shit together before the voice gives up and stops trying. Either way, we've got a woman whose youthful "learning from your mistakes" phase needs to come to an end.

Like "Los Angeles," it's something of a critique of a youth culture that glamorizes irresponsibility. It's not to slut-shame women for experiencing and enjoying a sexually active lifestyle, even with many partners if that's what they choose, but it does call into question thoughtlessly engaging in that kind of lifestyle without consideration of whether there might be other ways of living that actually make you happier. It's fine to sing "My Way" to yourself as you go through life, but at least make sure it really is your way.

This is the second flash story to appear in Pushcart this year. It's a good story, although if I were to compare the impact of "Los Angeles" and "I Figure," I'd say I found "Los Angeles" to pack a far stronger wallop. How could it not? With Emma Cline's story, I got to live for much longer in Alice's world (including actually knowing her name!) than I got to live in the world of Chinquee's nameless narrator. It's very hard to be changed by 800 words of fiction. You can receive a glancing blow from it, but not really a knockout punch.

Fiction is sort of like food. You can probably get a microwave meal that isn't terrible and that nourishes you in some way, but to really be satisfied, the food needs to marinate a bit. You need to actually be in the other world.

So why is flash fiction so prevalent? I think there are two reasons, one legitimate and the other maybe a side-effect of the flaccidity of American literature. The first reason is that flash teaches developing (and even experienced) writers critical lessons. It teaches thrift in language, it teaches how to focus on what matters, and it teaches the importance of focusing on tangible, physical manifestations of theme rather than abstract notions in order to tell the story. Flash is a good way to get better as a writer, so we might as well share some of those exercises, just like an etude written to improve musical technique might be interesting enough to play in concerts rather than just in a studio.

But flash's ubiquity might also have something to do with the sorry commercial state of American literature. Most journals survive on the very edge of financial viability, even with an all-volunteer staff and without paying contributors. The only money journals tend to get is from advertising, which is click-based, or from the occasional person buying/contributing to the magazine. (Other income sources include the interest from one-time donations and the entry fees from occasional contests.)

Clicks and contributions both tend to come from one source: family and friends of the people who are published in the magazine. You can get more contributors into an edition if each piece is short. Hence, the popularity of flash fiction.

It may have something to do with why Pushcart picked a few of them. The editors made a note in the introduction of saying they included more pieces this year than ever before. I'm sure a lot of Pushcart sales come from the social networks of writers. Any anthology is going to sell better the more writers it has in it. Flash is one way to get more writers in it.

I'm not really criticizing publishers or editors for doing this. I want hundreds of journals to survive, and they should do what they have to in order to stay alive. Pushcart is good for the careers of the writers included in it, so long may it live. If it's a choice for Pushcart between including two flash stories and being 505 pages long or not including them and being 501 pages long, they should include the two stories. But the inclusion does say something about the choices editors are having to make.

I don't mean to make less of Chinquee's story here, which is a good flash fiction story. But if you are picking the best 100 meals made in America in 2018 in order to serve them to people, you probably wouldn't pick two that were microwave dinners, even if the chef managed to do something with those microwave dinners that was ingenious, given the limitations. But reality has forced editors to put a few microwave meals on the menu.

Nearly every journal outside the elite top 50 or so has to deal with this reality. Even if they don't just accept flash, most have a word limit that tops out around 5,000. Since most journals now only exist online, it's not really a question of space, but it is a question of what their volunteer reading force can get through. Overworked readers are more likely to pick a short piece, because it takes less time to vet it. But by adapting in this way to the reality of the struggling marketplace of serious fiction, many journals are not giving readers what they really look for in serious fiction, which are the stories that take a little longer but are are totally worth it.

I can foresee anger from flash writers asserting that flash really can have as much oomph as a longer story. It can. I don't argue that. Borges has a number of short pieces that are right at the top of my list of stories I think about the most. But it is harder to really hit hard with that little space, and I think the big successes are less frequent. A chef who manages to make a microwave meal taste almost as good as a home-cooked one may be cleverer and more inventive than the chef who makes a meal taste good the old-fashioned way, but I still know which one I'd rather eat.

Kim Chinquee's "I Figure" hits similar thematic ground to "Los Angeles" by Emma Cline, which appeared in the 2018 BASS. Both stories center around young women, 20's-ish, who are making use too liberally of "you only live once" or "you learn by making mistakes, so make big mistakes" kinds of advice.

Chinquee's story is flash fiction, so it doesn't have much time to develop theme (or anything else). It relies on one scene and the imagery evoked in that scene. The narrator is lying on her back, post-coitally, balancing a glass of white wine on her abdomen while her lover the heart surgeon goes off to the bathroom to remove his condom and do the other after-sex things men do.

The act of balancing the wine glass tells the reader two things. First, she's in shape, because she's calling her stomach her "abs" and flexing in order to balance the glass. These are the sorts of things someone used to long rounds of ab exercises would do. She's likely someone who works out a lot in order to be attractive, rather than for personal reasons. We know she's had a lot of boyfriends, because she recalls taking a dog out "first with one boyfriend, then another, then another."

There are three refrains of "I figure" in the story. Twice it's to say she figures what she's doing is harmless. At the end, the formula shifts, and the narrator says she figures she's harmless. With each "I figure," the level of protesting too much grows.

It's a story of a woman making, perhaps, a few too many mistakes. The narrative arc doesn't happen on screen. We figure it will likely happen soon after this story is over. What we see in "I Figure" is a woman who's been deceiving herself, but her justifications are starting to become less convincing to herself. This might be the last time she does something self-destructive and calls it "harmless."

Or, maybe, this is the final act of defeating her own inner voice telling her to get her shit together before the voice gives up and stops trying. Either way, we've got a woman whose youthful "learning from your mistakes" phase needs to come to an end.

Like "Los Angeles," it's something of a critique of a youth culture that glamorizes irresponsibility. It's not to slut-shame women for experiencing and enjoying a sexually active lifestyle, even with many partners if that's what they choose, but it does call into question thoughtlessly engaging in that kind of lifestyle without consideration of whether there might be other ways of living that actually make you happier. It's fine to sing "My Way" to yourself as you go through life, but at least make sure it really is your way.

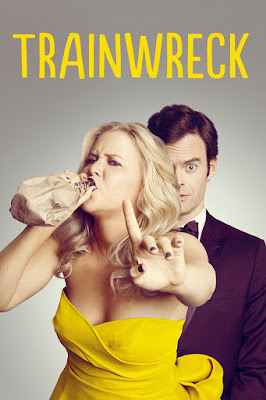

|

| Self-destructiveness is great for the audience, but for how long is it great for the self-destructee? |

Flash fiction in American literature

This is the second flash story to appear in Pushcart this year. It's a good story, although if I were to compare the impact of "Los Angeles" and "I Figure," I'd say I found "Los Angeles" to pack a far stronger wallop. How could it not? With Emma Cline's story, I got to live for much longer in Alice's world (including actually knowing her name!) than I got to live in the world of Chinquee's nameless narrator. It's very hard to be changed by 800 words of fiction. You can receive a glancing blow from it, but not really a knockout punch.

Fiction is sort of like food. You can probably get a microwave meal that isn't terrible and that nourishes you in some way, but to really be satisfied, the food needs to marinate a bit. You need to actually be in the other world.

So why is flash fiction so prevalent? I think there are two reasons, one legitimate and the other maybe a side-effect of the flaccidity of American literature. The first reason is that flash teaches developing (and even experienced) writers critical lessons. It teaches thrift in language, it teaches how to focus on what matters, and it teaches the importance of focusing on tangible, physical manifestations of theme rather than abstract notions in order to tell the story. Flash is a good way to get better as a writer, so we might as well share some of those exercises, just like an etude written to improve musical technique might be interesting enough to play in concerts rather than just in a studio.

But flash's ubiquity might also have something to do with the sorry commercial state of American literature. Most journals survive on the very edge of financial viability, even with an all-volunteer staff and without paying contributors. The only money journals tend to get is from advertising, which is click-based, or from the occasional person buying/contributing to the magazine. (Other income sources include the interest from one-time donations and the entry fees from occasional contests.)

Clicks and contributions both tend to come from one source: family and friends of the people who are published in the magazine. You can get more contributors into an edition if each piece is short. Hence, the popularity of flash fiction.

It may have something to do with why Pushcart picked a few of them. The editors made a note in the introduction of saying they included more pieces this year than ever before. I'm sure a lot of Pushcart sales come from the social networks of writers. Any anthology is going to sell better the more writers it has in it. Flash is one way to get more writers in it.

I'm not really criticizing publishers or editors for doing this. I want hundreds of journals to survive, and they should do what they have to in order to stay alive. Pushcart is good for the careers of the writers included in it, so long may it live. If it's a choice for Pushcart between including two flash stories and being 505 pages long or not including them and being 501 pages long, they should include the two stories. But the inclusion does say something about the choices editors are having to make.

I don't mean to make less of Chinquee's story here, which is a good flash fiction story. But if you are picking the best 100 meals made in America in 2018 in order to serve them to people, you probably wouldn't pick two that were microwave dinners, even if the chef managed to do something with those microwave dinners that was ingenious, given the limitations. But reality has forced editors to put a few microwave meals on the menu.

Nearly every journal outside the elite top 50 or so has to deal with this reality. Even if they don't just accept flash, most have a word limit that tops out around 5,000. Since most journals now only exist online, it's not really a question of space, but it is a question of what their volunteer reading force can get through. Overworked readers are more likely to pick a short piece, because it takes less time to vet it. But by adapting in this way to the reality of the struggling marketplace of serious fiction, many journals are not giving readers what they really look for in serious fiction, which are the stories that take a little longer but are are totally worth it.

I can foresee anger from flash writers asserting that flash really can have as much oomph as a longer story. It can. I don't argue that. Borges has a number of short pieces that are right at the top of my list of stories I think about the most. But it is harder to really hit hard with that little space, and I think the big successes are less frequent. A chef who manages to make a microwave meal taste almost as good as a home-cooked one may be cleverer and more inventive than the chef who makes a meal taste good the old-fashioned way, but I still know which one I'd rather eat.

Monday, March 11, 2019

Three kinds of alienation and the 2016 election: "Taco Night" by Julie Hecht

A brief digression: I'm back from a few days off from being "literature Jake," and I've resolved to at least finish analyzing the short stories from the current Pushcart Anthology before deciding if I want to keep doing this. Often in my life, I feel like such a dilettante. While I might be able to pull off an analysis of a short story better than your average college freshman, I'm not really an expert in the sense of being someone who devotes his whole life to literature. But whenever I start trying to become that person, I start to get pulled in the other direction--the other direction being my day job--in which I also do not feel I am a sufficient expert for the responsibility I have. So I vacillate back and forth between making literature my real passion, with the intent of one day also making it how I make a living, or thinking I ought to just, as Yoda would have it, keep my mind on where I am and what I am doing in my current career.

For now, as I said, I'm at least going to finish Pushcart, so on with "Taco Night"

I review stories from the Best American Short Stories collection and the Pushcart Anthology. The most recent edition of BASS was called the 2018 edition, while this version of Pushcart is called the 2019 anthology, but both are actually pretty close to each other in terms of the time periods in American literature they cover. The 2018 BASS picked stories for its anthology that were first published during a time that almost lines up exactly with the calendar year 2017. Pushcart is a few months later off this schedule, so it's not exactly lined up with a calendar year, but it's close. What I'm getting at is that this is the first edition of both anthologies that had a real chance to include a story that confronted the reality of Donald Trump's election in 2016. The last edition of both was too soon after the election.