Accusing liberals of being the thing they rail against is an old conservative trick. Some examples:

"Nobody is more intolerant than the so-called agents of tolerance."

"People who believe in a universe with no God criticize those who have faith, but doesn't believing something comes from nothing take the most faith of all?"

I'm hesitant to even appear to join in this kind of criticism, but to some extent, I find the comparisons between the sociology of religion and the sociology of political groups to be inevitable. My first committed ideology in life was evangelicalism, and even though I left it for good over twenty years ago, my experiences as an evangelical have shaped how I view all ideological communities since. Sometimes, when encountering some kind of interaction at the intersection of sociology and ideology, there's really no way to avoid the rather obvious feeling of deja vu.

To compare liberal political ideas and the behavior of the groups who hold those ideas to evangelicals or even to cults isn't entirely pejorative. To think it is demonstrates the kind of hardline resistance to facts liberals sometimes show, a resistance that makes them vulnerable to "liberals are hypocrites" kinds of attacks. (I say "them" about liberals, but I could say "we." I identify with liberal ideas more than I don't.) Of course groups founded on belief systems will show similar sociological and socio-psychological traits, even if some are founded on relatively more empirically defensible positions than others. To think that a community of humanists won't end up acting in many ways like a community of theists is similar to the kind of anthropocentric thinking that makes some people reject comparisons between humans and other animals. We don't want to accept that we're essentially of the same genus as other things, because we think it makes us less special.

Just because groups built around a shared liberal ideology might act in some ways similar to groups built around religious beliefs is not to say they're both the same in all ways, or that they're all equally invalid. Even if there is a large-sized overlap in sociological phenomena in the two types of groups, the differences can still be (and in my view, are) significant enough to make belonging to one group relatively more desirable than to another. But that doesn't mean we can just overlook the similarities, or realize that our group has many of the same problems internally that other kinds of groups do.

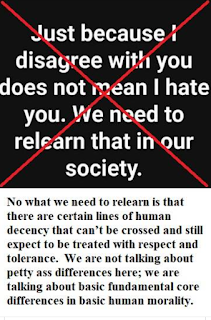

Since realizing I was a secular humanist and a political liberal in my twenties, I've certainly felt similarities between groups that share my beliefs and groups I used to belong to that shared my old beliefs. Here's an example. I saw this meme shared on the social media pages of two people, one a writer I follow on Twitter and one a liberal friend on Facebook:

In evangelical circles, there is a tendency to reject the idea that Christian belief (i.e. "the truth") shares much with ideas outside itself. That's a heresy, one that gives into the need to be accepted by the secular world. In reality, evangelicals believe, the truth and the world are so different that they will hardly agree on anything.

It's hard to know what issue the author of this meme had in mind. Had she been arguing with someone who really believed racial equality was impossible because some races were inherently better than others? What is the uncrossable line that was crossed here? I don't deny those lines exist, but I would deny that those lines are crossed all that often. Acting like those outside our group are nearly always outside the bounds of "human decency," however, tends to make our group's ideas stand out. It makes being a part of our group seem more urgent. It makes separation from the other group less a matter of intolerance and more a natural outgrowth of belief.

This "they're so wrong there's no way to find common ground" way of thinking manifests in other ways. Within Christian circles, there is always a debate between those who think it's worthless to try to "argue someone into the Kingdom of Heaven," those who feel that if a skeptic doesn't agree with you, it's best to walk away rather than cast your pearls before swine, and those who believe they have a responsibility to "give an answer for the hope that is in them." (That is, those who willingly will argue with skeptics and those who will not.)

In Christianity, for the most part, the apologists are winning that internal cultural war. I'm not saying your average Christian argues terribly well, but your average American Christian has at least memorized an opening argument on a number of objections a skeptic might raise to Christian beliefs. It feels to me, though, as though the "come out and be separate" crowd is winning in many political groups on the left. The idea that it's not worth engaging with conservatives is becoming more and more ubiquitous, with the basic rationale being that we shouldn't try to engage with someone who has "odious" beliefs.

What are these odious beliefs?

Not so long ago, the Republican Party in America was still the ideological descendant of the Reagan/Bush era. It was trying to figure out what "compassionate conservatism" meant. It wanted a kinder, gentler America. It gave us presidents who wanted an immigration policy most liberals agree with. It gave us a president who originally wanted to make education his top priority before 9/11 happened and changed the course of his presidency. It wasn't really a progressive party, but it was a party in dialogue with itself about whether conservativism and progressivism had some goals in common that conservativism could adopt for itself.

I'm not saying I agree with those presidents, but it's hard to see how the general drift of this kind of Republican's beliefs are "odious." I do not find the editorial stance of, say, The Economist to be odious. I don't find it beyond the bounds of human decency.

The general bounds of Reagan-era conservativism are still where a lot of conservatives are. That was more or less where Romney and McCain were. We as liberals had a right to object to much of the discourse: we might have disliked the jingoism, the willingness to reject spending on social programs but never to reject increases in military spending, the views on abortion meant to placate the religious base. We certainly were right to reject post 9-11 American adventurism (although most Democrats in Congress did not when it mattered). But that kind of Republican isn't odious. We were wrong to smear Romney and McCain with accusations of being racists. We realized, I hope, how wrong we were when a real racist came along and Romney and McCain were among the few Republicans willing to stand up to him.

Trump's rise took nearly everyone by surprise, including Republicans. There were different reactions among Republicans about how to deal with it. Some outright rejected Trump. Some wanted to try to guide Trumpism to better goals more in line with the last thirty years of Republican goals. Others jumped in all the way with the new wave, even when it wasn't clear what Trump stood for. Not all of these people, who might be the sorts of folks to disagree with you on social media, are odious.

We can't recognize heterodoxy in others because we don't recognize it in ourselves

It's hard for us to accept the plurality of voices opposing us, because we don't really accept the plurality of voices within our own community. Here's another evangelical sociological conundrum: should we define membership in our community in a narrow way, in order to ensure purity, or define it broadly, in order to bring more in? I don't think one side of that argument ever won in American evangelicalism as a whole, although one camp or another certainly won in some churches. (The church I went to as a teenager was a "Christianity, narrowly defined" kind of church.) But I do think that American evangelicalism realized that it couldn't grow by becoming so diffuse that it was nothing. There had to be barriers to entry in terms of professed belief. These barriers, ironically, probably led to growth, because the difficulty of getting in made people more motivated to stay once they had invested the effort to pass the barriers. Having somewhat tough requirements for belonging made members appreciate belonging more.

There is no church for political liberals. I mean, there are churches out there that largely share a politically liberal viewpoint, like the Unitarian Church, but nobody is required to be part of a church in order to be part of the ingroup of the politically liberal-minded. Nonetheless, liberals seem to have adopted some of the tougher barriers to entry evangelicals did, perhaps because liberals have seen the advantages this approach gave their political adversaries.

Liberals might, in fact, be drifting toward being even stricter than evangelicals. Maybe it's the lack of human connection a church gives that pushes us in this direction. In a church, you might think Robby drinks too much to be a good Christian, but you know the guy, and you played on the softball team with him, so you're willing to forgive him. That's not true of online liberal communities.

I generally tend to agree with liberal political ideas, but that doesn't mean I agree with every liberal orthodoxy of the moment. When I was an evangelical, I didn't agree with everything I was supposed to believe in order to be a member of most churches. My choices were to keep my mouth shut and stay a member or to say what I really believed and lose membership, even though at one point I still shared many of the group's core beliefs. It's not easy to stay part of the community as an uneasy, partly orthodox practitioner. At some point, it makes much more sense to just leave.

That's how I feel now as a liberal. There are some issues where I don't quite agree with what I feel like I'm supposed to agree with. It feels like too much of a risk, though, to say that I only agree with seventy percent of what I'm supposed to agree with, and here are my reservations about the rest. That feels like a one-way ticket to excommunication.

I'm not here to tell any liberal how to act online. I don't know the conservatives you interact with. Maybe the ones you know really are the odious kind. It's of course up to you and your own conscience how to interact online. This isn't meant to be a manifesto on what sort of philosophy liberals should adopt when it comes to questions of evangelism and fellowship. It's the feelings of one liberal, which I suspect are also the feelings of a lot of others. What I feel is that liberal discourse leaves me without a path to membership. The most I'll ever be is a protest vote for Democrats, because as not-at-home as I feel among liberals, I'm even less at home among conservatives. I don't think that's enough for a solid future for an ideology. There is always a balancing act between being open enough to allow people in and being strict enough that membership means something. Right now, I feel the balance is tipping in favor of purity in a way that makes me think I'm fine not being an active member.