I've long wondered what makes men do this. One of the short stories in my book, "Dawn Doesn't Disappoint," is about a man who takes up with a much younger woman, partly because I wanted to try to wrap my ahead around what makes a guy want to take up with someone much younger. But maybe it's not that hard to understand. "But youth looks good on everyone," my main character concluded after a list of his young girlfriend's flaws, and maybe that's all there is to it. It's hard for me to understand wanting a relationship where companionship is going to be difficult because of a lack of shared experiences and understanding, but maybe I'm overthinking it, at least for the men for whom that's not a priority.

The more difficult question, then, is why a young woman takes up with men like this. That's what "Erl King" by Julia Elliott examines. Much like my short story, the motivation can possibly be wrapped up in one phrase uttered by a character from the story: "suspension of disbelief."

The narrator, whose name we do not learn, because everyone only calls her pet names, has been raised like many young women. She's been surrounded by a cheap version of Romanticism, fed stories of princesses and castles, and her father has tried to keep her safe in her own home like it was a castle to keep her from her prince. When the narrator calls home at one point and hears her father in the background cutting down the weeds and wild vines growing up around the house, she recalls asking him as a child to let them grow. Why? So their house could "be like Sleeping Beauty's castle." The narrator grew up under a certain mythology in which fathers see themselves charged, like knights, with protecting the chastity of their daughters from would-be suitors.

While fathers think they're doing their daughters a favor, they're likely doing more to build up the romantic ideas of girls surrounded by myths of men coming to rescue them. The girls turn into young women programmed to look for a man to open the mysteries of the world to them. That's where the narrator and her three roommates, students at University of South Carolina, are at the beginning of the story. They take a break from their lives at home together to go to a party in the woods hosted by "The Wild Professor," who doesn't really even try to hide from his reputation. The young women are drawn to the party by "mutual longing."

|

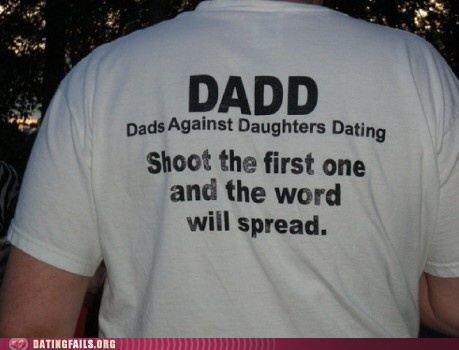

| I appreciate it when people self-identify as stupid on their shirts, so I don't have to spend the time to find out. |

Allusion storm

The story is dripping with literary allusions. I'm sure an enterprising literature student somewhere will follow the trail of allusions one day, but I'd like to avoid spending the next month of my life doing something that will only bore most readers. A great deal of the allusions are satirical. Many of the things said are pure nonsense, starting with the first words the narrator hears "theory guru" Dr. Glott say to the Wild Professor when she shows up at his house.

The short explanation of the significance of the allusions is that our young narrator has been brought up surrounded by romantic notions of men that make her susceptible to the Wild Professor's bullshit. Many of the references are to British Romanticism or the Germanic legends that fed Romanticism. (Karen Carlson did some really nice sleuthing of the first allusion encountered in the story here.) This works to sway the narrator in two ways. First, she's a literature student, and she's interested in learning more about what all the literature in the world means. The professor, she thinks, can help her to learn faster. "My ignorance was as deep as a wishing well, and the Wild Professor tossed glittering coins of knowledge into it."

Secondly, she's been conditioned to think of men Byronically. That is, women are to pity the suffering of the brilliant man who suffers for his brilliance. The Wild Professor is wild literally, as he morphs sometimes into a wild animal. This is the form he takes when he has sex with the narrator. The narrator can occasionally see through his transformations and view him in his real form, which is old and decrepit, but her "willing suspension of disbelief" usually wins out, and the old man transforms again. As a wild animal, he is something to marvel at and perhaps care for. She's basically Bella in the Twilight saga. Or any woman suffering with a drunk who says he wants to write the great American screenplay. All of this works to the Wild Professor's advantage when it comes to keeping her from leaving him.

The girl grows up

Our narrator inevitably outgrows the professor. The reason she took up with him in the first place was because it seemed he had a lot to teach her. And maybe he did, for a while. Since then, though, she's learned to transform herself, although she's done it largely by ignoring the way he does things and striking out on her own. The professor makes fun of her learning, but it seems to work. As she starts to outgrow him, the Wild Professor shows his true colors by starting to court someone even younger: the fourteen-year-old daughter of a philosophy professor. That's the moment the narrator knows she needs to leave, and she runs away with the young girl and her roommates in a White Rabbit (the car, not an actual white rabbit, although the image of the Wild Professor chasing a white rabbit is intentionally meant to make the reader think of every god chasing a wild maiden who then changes into an animal in various mythology systems).

Elliott got two stories into 2019 best-of anthologies. The other was "Hellion," which I loved. This story spent more time in the magical world and less in the real world than "Hellion" did, and maybe for this reason, it didn't feel as poignant to me. But that's not the point of the story. It's satire, and satire isn't usually aimed at making the reader cry from emotional catharsis.

What this story does, it does well. Like a good satirical article from The Onion or McSweeney's, the reader kind of gets the joke early on and has a sense of what's coming from the opening. The story then commits to the joke, goes a little overboard with it, delighting the reader with excess, then ends the bit just as it's about to wear thin. What makes the story special isn't that it gives a new understanding to these May-December romances, but that it is so good at taking what is the obvious but probably correct understanding of them and finding a perfect vehicle to express it. After finishing this story, the reader will think, "Yeah, that's exactly what these relationships are about," and maybe be unable to ever think of them again without recalling this story.

I've never considered myself really a fan of this kind of thing, but Julia Elliott really has the knack for drawing me in.

ReplyDeleteIf there's going to be magical realism, I like when I can at least have some sense of what the magical parts represent, which Elliott graciously does.

Delete