Would it surprise anyone if I said that a North Korean novel skirts a bit with falling into propaganda? Probably not, but in spite of the extreme limitations of its culture on artistic freedom, the novel "Friend" (벗) by Paek Nam Ryong is full of surprises. Reading it, I was reminded of the opening scenes of the 1976 Argentinian novel

Kiss of the Spider Woman, when Molina is recounting films he likes to his cellmate Valentin as a way to kill time. Molina likes a Nazi propaganda film, one that in many ways resembles the work of Leni Riefenstahl. Valentin is appalled by this, but Molina, who is in prison because as a transgender woman she is seen as a corrupter of public morals, believes that beauty is beauty, and it doesn't become less so because the creator of the beauty is using the only opportunity society offers her to make it. Molina didn't use these words, but there is a sense in which beauty, in a society that surrounds us with ugliness, is transgressive.

Transgressiveness is a term that gets kicked around in art a lot. It just means art which violates the mores or sensibilities of the culture likely to consume it. We're so used to transgressive works in the West now that it's difficult for some artists to even figure out how to shock anymore. But it's not like that in some societies. The list of societies where one doesn't just go around shocking sensibilities would have North Korea at the top of it.

So it's surprising that Paek's novel, published in 1988 (and recently translated into English, which is how I heard of it, although I read the Korean version, not the translation), manages, in fact, to transgress. Its transgressions are like those of Molina's fictional Nazi film: they aren't open transgressions, but rather they exploit the very ideals the society professes to believe to be noble in order, by juxtaposition with reality, to highlight how that society is not meeting its own ideals. Beauty stands out among ugliness.

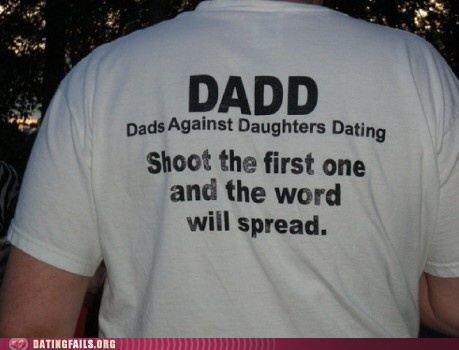

|

| The title of the novel, translated "friend," is pronounced "Butt," which always makes me giggle. |

If the novel really does include transgressions mixed in with its generally pliant, pro-government, pro-party, pro-socialism exterior, it's a funny kind of transgression. It's to be expected, I suppose, that a novel from a society like no other would produce novels like no other, including the transgressive parts of those novels. South Korean writer Jeong Do-sang, in his analysis of the

Friend, commented on the uniqueness of the book as its most salient characteristic:

"The North Korean novel had not been influenced at all in its development by Russia or China, much less Europe, and has become a truly unique colloquial novel. South Korean novels are greatly influenced by the Japanese auto-biographical novel or French novels, even while it could be said they still maintain their own particular qualities. By contrast, one cannot get away from the suspicion with North Korean novels that they exist only to correspond to the society called "the nation." Within society, the individual exists only as a cog in the machine, and the characters in their art are not much different."

The North Korean novel that would have once fit perfectly into a family-friendly American TV lineup

What does transgressiveness in a North Korean novel look like? Not much different from a family-friendly drama from the late 80s or early 90s in America, actually. I could see it as a show called

Divorce Judge, in which a mild-mannered civil court judge takes it upon himself to save the marriages of the couples who show up in his court, filing for divorces. It would have fit right in with

Highway to Heaven or

Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman.

Jong Jin U is the judge in this drama. Chae Sun Hui is a stylish but distraught woman in her thirties who shows up one day asking for a divorce. Her husband, Ri Sok Chun, has not come to court with her, but she assures Judge Jong that he's okay with the divorce. He just doesn't want to have to deal with the disgrace of going to the court to work out all the details.

Rather than just make a ruling based on what is presented to him in court, Judge Jong decides to go investigate. He talks to a number of people who know the couple: Ri's boss at the factory where he works on a lathe; Chae's choir director; the village party chief. He also hears from a high-ranking distant relation of Chae's who encourages the judge to just give the couple the divorce they want. (Annnd, I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the scene where he goes to the family's house and finds their child alone and possibly coming down with a cold, so he takes the child home with him in the rain, then strips the child down and puts him in a hot bath. Not everything in the novel would have made it past American TV censors. Even in the 80s, I hope that would have raised some red flags.)

|

| Landon was a weird guy, but not bring-a-neighbor's-child-to-your-house-and-give-him-a-bath weird. |

Instead of taking the easy way out, Judge Jong keeps digging. He finds out that Chae has become a little bit haughty since she joined a traveling singing group, because she has gotten used to being cheered and awarded. It's made her despise her blue-collar-factory-man of a husband. The husband is simple and hard-working. After years of late hours and setbacks, he created a "multi-axes screw press" (다축라사 가공기--I don't know enough about machines to know what the right translation is, but it's some kind of machine used in his factory). His invention won third place in a contest, but his wife couldn't care less. She thinks his inventions are a waste of time and the family's resources.

Ri Sok Chun isn't blameless, though. He's simple and hard-working, but he refuses to better himself by going to night school like his wife tells him to. Although he's naturally gifted, his lack of a formal education has kept him from greater success with his inventions.

Judge Jong eventually has a tell-it-like-it-is tete-a-tete with both Ri and Chae. Ri accepts the judge's advice more readily than Chae does, but in the end, they reunite. Along the way, Judge Jong--the B story in his own drama--reconsiders his own attitude toward his wife, whom he sometimes resents for her work that takes her away for long stretches, making him a geographical bachelor. There's also a brief C story about a drunk and a school principal, and Judge Jong fixes that marriage, too.

So orthodox, it's heterodox

For the most part, the novel contains nothing in it that would scandalize a North Korean readership. Indeed, the novel did well when it came out in 1988. It even sold well in France a few years later when it was translated. It can only be viewed as a success from the point-of-view of public perceptions of the North Korean government.

However, the novel contains seeds of transgression in it, not from challenging the orthodox view of the party, but by agreeing with it so fully, it puts into question how party officials actually behave in the real world. Here are some of the values the novel supports, some of which are expected and some of which were a little surprising:

Unsurprising: The family is the smallest organic unit of society. Judge Jong calls the home "the small society called a family." It's society in miniature. This actually isn't that far off from how Western society has viewed the family for centuries, and the novel takes a very positive view of the family. The final line of the novel reads: "The home is is a beautiful world where human love lives and the future grows."

Unlike in the West, where we believe so strongly in the sanctity of the family we feel the state should be limited in its ability to intervene, the very importance of the family is the reason the state needs to intervene, both for the good of the family and the good of society. If the family is the most basic building block of society, then what happens in one family affects everyone. When refusing to easily grant a divorce, the judge explains that, "The family belongs to the individual, but causing harm to a family is not an individual issue. It's a social issue that many people in the village, the community, and the workplace should care about."

It's a formula that prevents even the sanctity of the family from being able to trump the will of the state, all in the name of the good of the family. The law isn't concerned with just the law, but public morality. The idea of the absolute importance of public morals--which hardly even exists in the West now, we are so used to thinking of morality as an individual issue--pervades the book. It shows up on the first page. The building where the judge decides cases is "not a place that handles beautiful or positive deeds." The narrator also tells us that, "People in the area who live by healthy, moral economic principles and social ethics, who have harmonious homes," wouldn't need to go there, so many don't even know where it is.

There's an element of natural law to this: the novel wants the reader to believe that a harmonious marriage comes with living in accordance with moral precepts, and that these moral precepts are obvious and natural. There is an almost Gothic coincidence in the novel between weather or scenery and the moral rectitude of the characters. When characters are seeking divorce, it's rainy and ugly. When they love each other, it's beautiful.

By associating the harmonious family with nature and nature with public morality, the novel asserts the state's right to intervene in order to restore the natural order of things.

Unsurprising: The key to a moral life is self-reflection. Thae Yong Ho, former North Korean Deputy Ambassador to the UK turned defector, said that it was impossible to understand North Korean life without understanding the life evaluation (생활 총화). At least weekly, North Koreans gather with their work units to criticize each other and themselves. (Korean speakers, there is

a good explanation of the topic here.) It's like Catholic confession, but everyone's invited.

In the novel, Judge Jong's criticism of Ri and Chae is what helps them to transform and improve. It also transforms the drunk, the evil committee chairman who tried to ruin the couple's marriage, and Jong's own self-reflection even improves his own attitude about his marriage.

Western literature has long thought of art as a mirror. When Jong criticizes Chae, she sees his accusations as a mirror, but not in a pleasant way: "The judge's expression, soft but piercing, came to her again, and his words, like a surgeon's knife to her heart, rang in her ears. The judge's keen insights shone like a mirror. That mirror showed the flaws inside or her, a clear mirror into her own psyche, like a diagnostic laser."

The judge stresses to both Ri and Chae that he's telling them this as a "friend," not as a judge (hence the title of the book), but it has the same effect as if a judge had said it for both of them.

Surprising: Except sometimes, family does trump the state. Judge Jong admires Ri's work ethic, but tells him that it's not totally unexpected his wife would be unsatisfied with him. As a man, he is responsible for the family's economic health, which means he should strive to provide them with more--which sounds like an incredibly Western idea. Ri should listen to his wife when she tells him to go to night school and try to be more than just a lathe operator. He chides Ri for not approaching family life with the same dedication he does to work in the factory. "The family may be small, but it's your own world linked to society." He tells Ri he is "only sacrificing for the factory and society by working and inventing, but undervaluing his own wife." The same logic used earlier to subjugate the family to society is also used to place the family in at least equal importance.

Surprising: The novel is, in some ways, kind of progressive. When Judge Jong lays into Ri about not striving for more, he accuses him of "a kind of conservatism." Ri can't just stay where he is. The good of the country depends on people wanting more out of life. Again, this is an incredibly Western, almost market-driven-rewards-based-motivational talk here. North Korea will be a city on a hill, but only if the people are as focused on improving themselves as they are the country. Even though it's phrased as for the good of the country, it's a dangerously individualistic way to frame it, because it seems to nearly equate self-improvement with societal improvement, meaning people should be encouraged to follow their own interests.

Even more surprisingly, the novel has a go at at least one high-ranking official. The only bad person in the novel is Chae Rim, the "business technology committee chairman," whatever that is, who is a distant relation to the wife Chae Sun Hui. His position of authority gave Chae Rim the ability to get Ri's invention bumped from first prize to third, which helped stir up his wife's frustration with her husband's inventions and him in general. When the judge realizes what happened, he threatens to throw the book at Chae Rim. The judge muses at one point about how he can't believe such people exist: "Why are there people like that? Hollow people who do not respect the sacred truth of how the country values economic advancement as if it were life itself. And that he rose to a position of administrative authority in technology!"

Criticizing by praising

Paek's novel is standard stuff in how it views North Korea as a paradise, or at least a paradise in the making. It's set in the late 60s or early 70s, which many North Koreans still think of as the golden age of North Korea. That very idealizing of North Korea, though, can itself be a challenge to the status quo, if the status quo is really not living up to the ideals. While seeming to reiterate the propaganda of the country that North Korea is a worker's paradise, it also deconstructs its own paradise, both by asking why imperfections are allowed into paradise, and also by setting a standard for officials that few actual officials meet.

Judge Jong's almost comic-hero-like dedication to duty will surely stand out as far exceeding any official anyone in North Korea knows. Regime censors might see Jong as either a goal for officials to strive for or pure propagandizing, wish-fulfillment fantasy for an official who doesn't exist in the real world. But it won't escape readers that there are a lot more Chae Rims in their world than there are Judge Jongs. The novel manages to demand better of officials by simply repeating what the regime is already telling everyone those officials already are like.