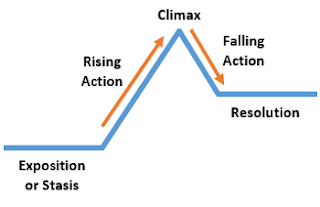

Very early in the literary education of most students in America, they learn about narrative arcs. The most typical model students come across uses a diagram that looks like a roller coaster, with a gradual climb upwards, followed by a sharp descent. In the most commonly taught model, we meet a character in their "before" life, witnessing what life is like just before the force that changes the status quo for the main character and gets the story moving enters the plot. In Bridge to Terebithia, for example, we watch Jesse wake up to his normal life on the first day of school, with his indifferent father, annoying sisters, and his dreams of being the fastest kid in school. Then we meet the new girl in school, who changes the trajectory of Jesse's life, which gets the story going.

Once the story gets going, there is rising action. Eventually, the plot heats up enough that it boils over, giving us the climax, after which there is a change in the main character, leading to a falling action and a new reality, which is where the story ends.

|

| Shoutout to my 8th grade teacher, Mrs. Stutchel, whom I and everyone else hated. She taught this, but I didn't learn it from her. |

The thirty-six stories in Luke Rolfe's "Impossible Naked Life" (Kallisto Gaia Press) aren't interested in any of that climax and change stuff you learned in middle school, though. Over and over, there is a chance in these stories to achieve a climax, but the climax is deferred or avoided. When there is a climax, it's almost invariably a bad one. If the climax in a story is like the orgasm in sex, then these stories are the ruined orgasm fetish of short story collections.

This isn't a criticism. The avoiding and maneuvering around climax is skillful and intentional. Most of us never experience true (non-sexual) climaxes in life, or epiphanies that lead to meaningful change. That's an artifice of literature, and while neither I nor any other reader will ever tire of the formula, that doesn't mean every story has to hold to it. When something interesting happens to most people, they either change only slightly or don't change at all. So Rolfes is playing with a different and interesting aesthetic here. The trick is whether he can be that close to real life and still delight the reader.

Romantic realist

There are far more stories in this collection that feature a romantic relationship that never fully develops or that falls apart. My rough count yields eleven of these ("Crab," "Day Camp," "Plucked," "Fish Heart," "Siren," "Liar, Liar," "White Landscaping Rocks," "There, There," "Acai Bowl" (maybe), "Time Magazine Person of the Year," and "Common." There are only maybe two stories with romances that seem to be going anywhere at the end, and I wasn't even sure about those two.

Romantic comedies are the best known genre for mixing the character overcoming conflict at the moment of climax with the fulfillment of the achievement of romance. They aren't the only types of stories that do this, though. Coupling the main character working through his main flaw in order to overcome adversity often is shown in the character's ability to achieve the love interest they've been chasing.

These stories just don't work that way, though. Even stories that end on a note of sweetness seldom end with "boy meets girl" (or "girl meets girl," which is what we might have in one of the few exceptions in this collection). These stories reject both climaxes that change characters forever and romances that lead to happy-ever-after. It's a brutally honest collection in that sense.

Anticlimactic climaxes

"This story doesn't have an ending," the narrator of "White Landscaping Rocks" tells us, and that could be said to be true of many of the stories in the collection. Moreover, there is one story after another that seems to portend a big, climactic, orgasmic moment, but that moment never comes. "There, There" teases a storm that never materializes. "Karate Witch Teacher Kickass" has a narrative that build to a fight that never comes. "Showdown" brings up the notion of Mike Tyson fighting an alien to save the human race, but the scene fizzles out like a daydream interrupted.

This aversion to climax is often literal. There are several sex scenes that begin but are then interrupted. In "Plucked," a struggling college student connects with an older woman on a train. They end up in her private sleeping room, but after kissing that seems to be leading to sex, the woman just runs out of libido:

"After a while, she says, "I'm too tired to keep going."

"We can do whatever you want to do," I say.

"Sleep. I want to fall asleep."

Similarly, "Fish Heart" has a scene in which a woman is making out but not enjoying it, while "Killer Saltwater Crocodile Killer" briefly alludes to a budding romance that died before going anywhere. A paperboy in "Paperboy" sees a couple naked in their front window, but rather than going at it, he sees that "they seemed to be just standing there, hugging each other as the sun rose across the neighborhood."

As if aware of its own refusal to give readers the endings they're used to, one story in the collection has a character recall an old story he once wrote, only to have another character offer the critique, "That ending is terrible." The story-teller responds, "It's my story...I can end it any way I want."

Climax is dangerous

Sex is...bad?

Sex is more often spiritualized, as in the scene on the train in "Plucked" or the two unlikely teammates huddling together for warmth in "Impossible Naked Life."

Nature is...bad, too?

It isn't just sex that these stories tend to eschew; it's also nature and natural impulses. In "Bubbleheads," Sunny wants her friend Jenny to close her eyes and drive by "instinct," but this ends as badly as you'd think it would. "Instinct," in fact, isn't human in these stories. It's animal, and not in a good way. A saltwater crocodile's instinct is to kill and eat: "That's all an animal lives for. The next day. The next meal. The chance to prolong its life."

Because nature's tendency is to kill and eat, much of the natural imagery in the anthology is a threat. There are crocodiles and alligators and spiders. In "Viper," there is a deadly snake at the head of a walking trail, which is perhaps the furthest point the natural world can be said to reach into the manicured world of human development. It's not the only snake that shows up in these stories. "Rubber Horsey Heads" is a story that's little more than a narrated nightmare, full of animals out to get humans.

The only "instinct" the text approves of in any story is the instinct for self-discipline Genevieve exhibits in the title story, which notes she has "a natural instinct at patience and holding still." Self-control is more important that self-expression. It's an anti-Romantic aesthetic.

The Ego controlling the Id

It's not so much, maybe, that sex and natural urges are bad as it is that they're associated with what we've come to call the Id. These are the base, reptilian urges of the brain, the raw, animal urges connected with survival and maximizing pleasure. It's the caveman brain that tells us to murder our enemies and ravage their women.

These stories are leery of following our natural urges to their climatic conclusions because the Id tends to lead to death and destruction. Instead, these stories--at least most of the happy ones--feature characters whose Egos (their socially aware brains) subsume their Ids. In "Hold your Soul," we find a child urging her teacher to take care of his soul, a rather spiritualized suggestion of prioritizing the spiritual over the carnal.

Salvation isn't found in these stories through diving deep into the psyche to "find oneself." In "Ball Pit," two characters dive deep into a fantastically deep children's ball pit, which serves as a metaphor for the depth of the subconscious. What they find is terrifying, which suggests that perhaps there are some psychological depths better off not plumbed. Self-revelation doesn't lead to anything good, which is why, in spite of the evocation of nakedness in the title of the book, nakedness tends to be something to avoid in these stories. "Killer Saltwater Crocodile Killer" mentions characters and their "amount of nakedness they were ridiculous enough to endure on that particular weekend." Nakedness isn't part of self-discovery leading to wisdom. It's coupled, instead, with ridiculousness.

In the title story, about a woman on a reality show where contestants try to survive while naked in the wild (similar, I think, to Naked and Afraid), we finally confront nudity head-on. The nakedness is portrayed, however, not as natural, but as artifice. Nothing is more fake than the "reality" show, and Genevieve comes to wonder what the point of all the nakedness is. While "impossible naked life" is a phrase only specifically applied to the last and title story (which might be the best in the book), it could also apply to the whole of the book (as we should think it would, given that this is the title of the collection). It's impossible to live life nakedly, or practicing extreme self-revelation or self-knowledge. A little repression is what separates us from crocodiles.

The title story is interesting in that it seems to confirm the themes of many of the other stories, but in a reverse way. There is frank nakedness and introspection, and eventually, the two characters do share their inner selves and are emotionally vulnerable. This is only achieved, though, once the two characters come to a place where they are uninterested in nakedness, where it now seems too ridiculous to think of. It's a reverse story of Eden--the characters are no longer ashamed of their nakedness, not because they've decided to embrace their nudity like Romantics, but because they've demonstrated control enough to simply not find it that interesting.

Manly men aren't the ideal

Perhaps because the Id is shown as something to be held in check in these stories, manly men are generally held up as objects of scorn. In "V Scale" (one of the two stories that might actually end with a romance that's going somewhere), the main character avoids gyms with men grunting as they strain to lift weights, which she is sure is something they only do to show off. There are other insults in the book thrown at weightlifters. In "Puffy Man," a weightlifter at an outdoor gym near the beach is seen as a monster by a young girl. "Man Show" is about two young men who are obsessed with their bodies and how self-centered and unaware this makes them. We are meant to sympathize more with the skinny runner in "Palestine Boy" than with the giant football player who tries, clumsily, to connect with him. The physical ideal isn't a strong man who can push obstacles out of the way, it's runners who endure or rock climbers who patiently work their way through puzzles.

Living in the midst of our world means avoiding the fireworks

Perhaps the single best image in these stories of how to survive in a world full of death and sadness comes at the end of "The Birds of Joy." In a medical facility where patients are dropping like flies, one dying woman finds happiness in a bird that's snuck into the facility. But rather than fly to the heavens, like we'd expect in a normal narrative cycle, instead we see the bird choosing to "settle into the bedpan, uninterested in flight."

The narrative arc in these stories could possibly be drawn as follows:

|

| Verily, my MS Paint skills know no bounds |

These stories are occasionally weird, but not terribly so, and most tend toward realism. Even the ones that bend realism, however, are still thematically grounded in reality, because they are trying to break the habit in readers of looking for vicarious catharsis. Even at their most fantastic, the point is that we shouldn't look to the fantastic to heal us, because the fantastic doesn't happen all that often. What does happen to change our lives for the better is our decision to control our worst impulses. That's not as fun as fireworks, but it's a lot more effective. This collection deserves praise for its ability to refuse the well-trod path of fireworks.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Feel free to leave a comment. I like to know people are reading and thinking.